They Did Check It Out. That’s What Makes It Worse.

A response to “Why didn’t the council investigate?"

Following publication of my article on the Johnson Street fire, a reader asked: “Why did no one from the council check it out?”

The answer is more disturbing than regulatory neglect.

They did check it out.

They conducted almost a year-long investigation.

They made site visits. They reviewed evidence.

And then they claimed to find nothing.

This isn’t a story about authorities failing to investigate. It’s about what happens when investigation becomes a tool for managing complaints rather than addressing harm.

What Actually Happened: A Timeline

March 2022: I contacted Ealing Council about incinerators at Sam’s Recycling and neighbouring units on Johnson Street, asking whether environmental permits were in place.

March 2022: The Council’s Environmental Protection Officer responded that the business didn’t require an environmental permit, and that there had been “no complaints” between April 2017 and June 2021.

He added reassurance: the council had appointed a dedicated Environmental Health Officer conducting ongoing assessments since late 2021. The outcomes “support findings of historical complaints data.”

In other words: We’re investigating. We’ve found nothing.

August 2022: After experiencing strong burning plastic odours entering my home, I visited the site and submitted:

- Photographs showing open burning

- Video evidence of poorly managed operations

- Written testimony documenting burning of treated wooden pallets and melamine-coated particle board

- Evidence of unrestricted public access from residential street where children play

I explicitly noted the site appeared to be “effectively an open fire” with serious fire risk implications.

September 2022: No response. I requested acknowledgement.

October 2022: Council response arrived. The Environmental Protection Manager explained:

“Council’s odour assessments, between Sep 2021 and June 2022, have not identified or witnessed presence of statutory nuisance at the complainants' addresses.

“The council had conducted almost a year-long daily investigation in response to complaints (though they’d previously stated there were “no complaints”). Despite this year-long effort, investigating officers were “unable to verify any odour nuisance, or enforce better practices.”

The council would, however, write to businesses requesting they explore “additional best practicable means” to reduce emissions.

November 2022: I requested a copy of this letter. No response.

February 2023: Three months later, still no response. I visited the site again and reported the incinerator at Sam’s Recycling appeared to have been enclosed with corrugated sheets - possibly removed or being replaced.

March 2023: Council responded with links to Environment Agency permit registrations for the sites. However, as I noted, these permits didn’t mention waste incineration or incinerator use.

August 2023: After nearly 18 months of correspondence, I summarised my understanding in a detailed email. Point 15 stated:

“It seems to me that your investigative techniques, however improved you claim them to be, aren’t actually any good at all, and perhaps are designed to be that way. After all, if you could ‘verify’ what I and other residents tell you, then you might have to take enforcement action.”

September 2023: No response. I requested acknowledgement.

January 2024: I escalated to formal complaint, noting it had been over four months since my August email with no acknowledgement, “let alone any response.”

According to the council’s complaints policy, I should have received acknowledgement within four days and a Stage One response within twenty days.

January 2024: Three weeks later, still no acknowledgement. I noted the breach of complaints policy.”

January 2026: A devastating fire guts the site causing over half a million pounds worth of damages according to the owner when I spoke to him.

The Investigation That Found Nothing

So what happened during that almost year-long “daily investigation” between September 2021 and June 2022?

According to the council:

- No evidence of statutory odour nuisance was identified

- Officers were unable to verify any odour nuisance

- Officers were unable to enforce better practices

- Initial indications suggested odour intensity and chemical concentrations were “well below national and international standards”

Meanwhile, in just two or three visits made in response to strong burning plastic odours entering my home, I documented:

- Open or poorly enclosed incineration

- Burning of treated wood, melamine, and plastic waste

- Smoke plumes affecting residential areas

- Unsafe waste handling and storage

- Explicit fire risk from poor management

- Unrestricted public access where children play

The Methodology Gap

How is it possible for a year-long daily investigation by trained professionals to find no evidence of problems that a resident documented in three visits?

Three possibilities:

- I fabricated evidence.

The photographs and video are fake. My written testimony is false. The burning plastic odours I and my neighbours experienced were imagined.

- Council investigators are incompetent.

Despite being trained Environmental Health Officers, despite having dedicated resources, despite a year of daily monitoring, they genuinely couldn’t detect what untrained residents could document in hours.

- Investigation techniques are designed not to verify harm.

As I suggested in my August 2023 email: if investigators could verify what residents report, they would have to take enforcement action. Better to conduct investigations in ways that consistently fail to establish statutory nuisance thresholds.

I don’t believe I fabricated evidence. My photographs exist. The fire occurred exactly as the evidence suggested it would.

I don’t believe council investigators are universally incompetent. Some may be excellent at their jobs.

That leaves the third option.

What “Investigation” Actually Means

The year-long investigation wasn’t designed to establish whether harmful practices were occurring. It was designed to establish whether those practices met the specific legal threshold of “statutory nuisance” sufficient to trigger enforcement action.

These are not the same thing.

Harmful practices can continue indefinitely without meeting statutory nuisance thresholds, particularly when:

- Investigation methodologies require direct witnessing at specific moments

- Odour assessments depend on subjective officer judgment at time of visit

- Chemical monitoring is time-limited and may miss peak exposures

- Regulatory frameworks create jurisdictional confusion

- “Best practice” letters substitute for enforcement action

- Complaints are acknowledged but not acted upon

The result is a system that generates impressive paperwork - year-long investigations! Daily monitoring! Coordination between departments! - while ensuring harmful activities continue until catastrophic failure forces intervention.

The Pattern Across Southall

This isn’t unique to Johnson Street. It’s the same pattern documented across multiple pollution cases in Southall:

FM Conway: Dr John Freeman, council’s former air quality officer, admitted at a September 2018 Air Quality Scrutiny Panel meeting there had been a “lack of scrutiny” of this operator. Despite “a considerable body of complaints,” enforcement remained elusive.

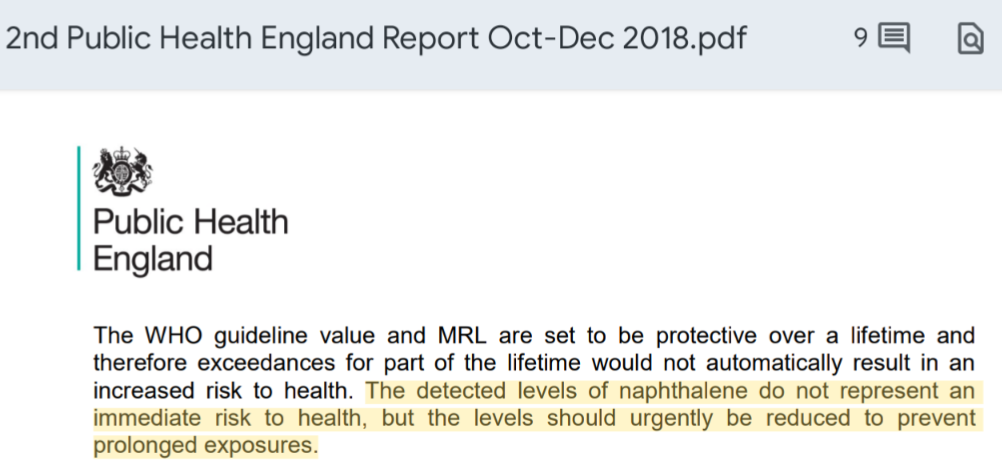

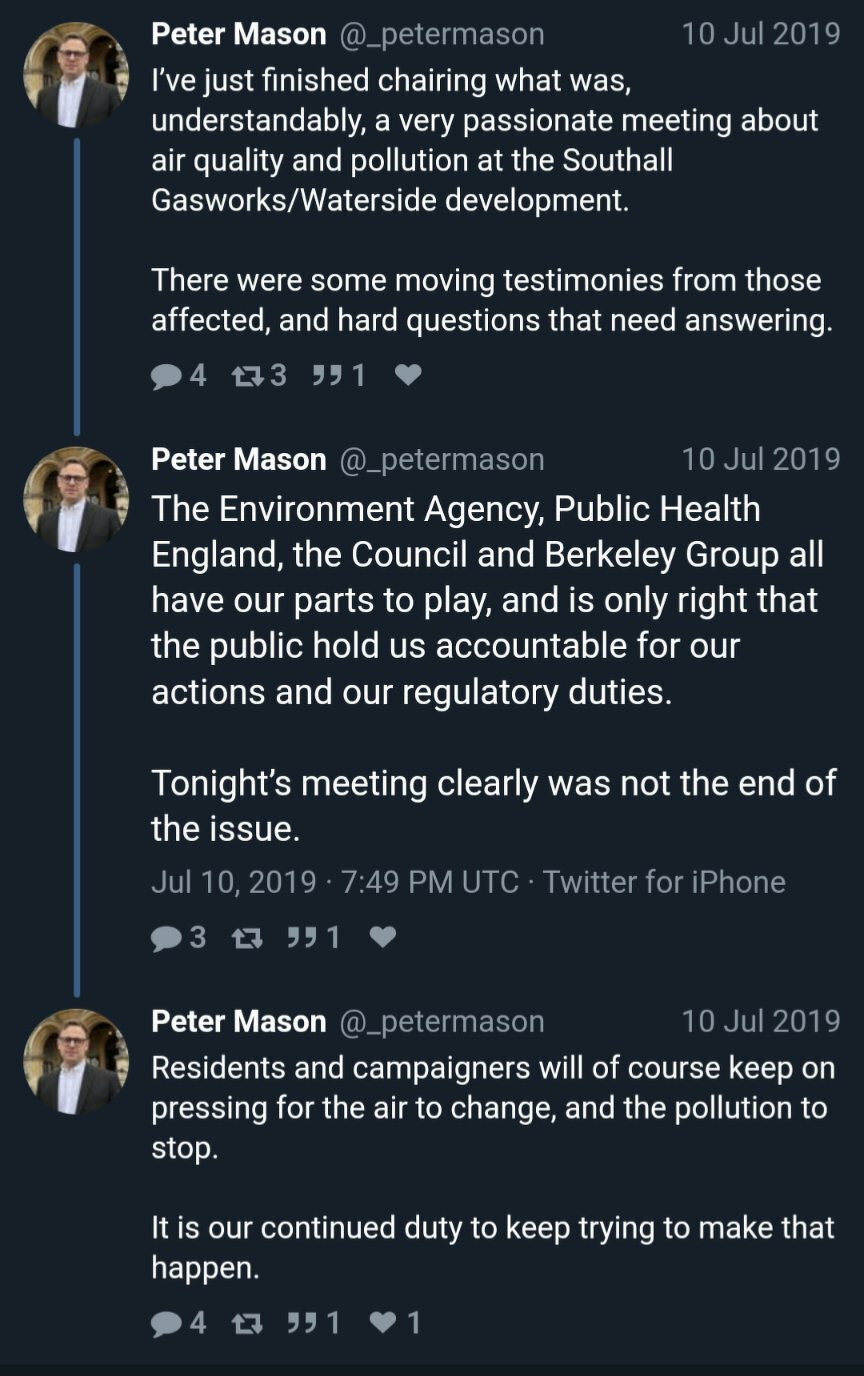

Southall Gasworks: Between 2017-2020, residents reported severe respiratory symptoms, hospitalisations, and toxic odours. Public Health England eventually acknowledged naphthalene levels required “urgent reduction” - but only after I pointed out at a public meeting that localised readings were consistently above legal limits, contrary to the “site averages” PHE had presented suggesting no harm.

— My son was hospitalised three times with asthma in 2016-2017 when gasworks remediation began. The headteacher at Blair Peach Primary School reported to governors that “very strong smells from the gasworks site caused asthma and headaches.”

PHE’s final position: no physical harm occurred, though they acknowledged some residents experienced anxiety about exposure (implying psychological rather than toxicological harm). This despite later admitting naphthalene levels exceeded safety thresholds when examined at neighbourhood level rather than site-wide averages.

Johnson Street: Year-long investigation finding no evidence of problems. Site continues operating. Fire occurs exactly as residents predicted.

The Class and Race Context

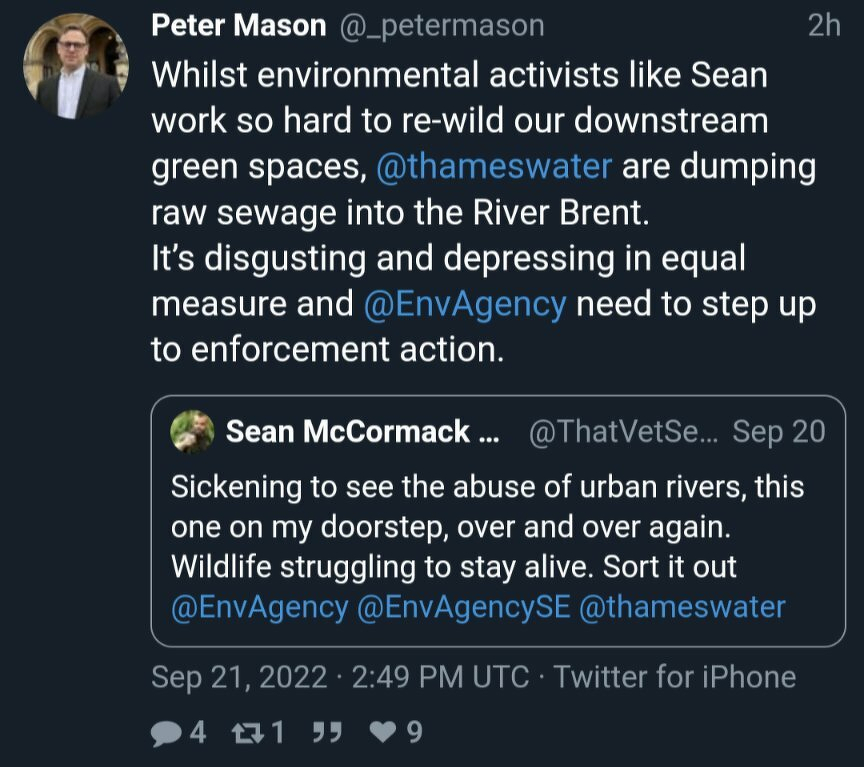

In my formal complaint, I drew comparison with Council Leader Peter Mason’s response to different pollution incidents:

“My reason for sharing Peter Mason’s breathless twittering about the poisoning of the Brent River was not for you […] to do anything about it, but simply to highlight the disparity between how people in Southall are treated when we complain about poison air from Mason’s MIPIM party sponsors, and how eels are treated by our new council leader and Southall Green ward councillor.”

When eels in the River Brent faced toxic exposure, Mason tweeted demanding immediate enforcement action against “disgusting and depressing” pollution.

When predominantly Black and Asian residents of Southall reported toxic air exposure, hospitalised children, and explicit fire risks, the same council leader consistently stated no enforcement action can be taken.

This isn’t accidental. As I noted in my complaint (and in my formal and comprehensive response to Ealing’s air quality strategy consultation - which was, of course, unacknowledged and ignored):

“It is now widely acknowledged that BAME people are more likely to suffer the ill-effects of air pollution, so this should be treated as a potential health emergency, particularly by a council which has such a poor record with equalities as highlighted so profoundly by Lord Woolley’s Race Equality Commission Report last year.”

In 2022, Lord Woolley’s Race Equality Commission warned that race inequality was “a crisis demanding urgent response” and explicitly called for a public health approach to structural harm, stronger community trust, and real accountability.

Yet when toxic smoke from the Johnson Street recycling yard fire spread through a predominantly BAME residential area, the council response followed the same old institutional pattern: delay, fragmentation, minimal enforcement and no visible precautionary public health intervention.

The gap between Ealing’s commitments and its actions is not abstract. It is measurable in hours of smoke exposure, unanswered resident concerns, and a regulatory system that still reacts procedurally and defensively, instead of protecting communities proactively, or indeed collaboratively.

Southall has nearly a quarter (23%) of the top 30 GP practices in London where asthma treatment is most prevalent. The community is characterised by high asthma rates, prolonged exposure to cumulative industrial and transport pollution, poverty, and predominantly Black and Asian residents.

When harmful environmental practices occur in such communities, investigation methodologies that consistently fail to verify harm don’t operate neutrally. They operate to enable continued harm in places where residents' testimony is systematically discounted.

The Gove Letter

In my August 2023 email, I included a quote from then-Housing Secretary Michael Gove’s letter to Ealing Council’s Chief Executive Tony Clements regarding a separate failure:

“You have failed your resident. Everyone, particularly those who are vulnerable, should be able to expect to have their complaint taken seriously.”

Gove noted this indicated “wider organisational culture at the council.”

The Johnson Street fire - occurring 30 months after explicit written warnings, photographic evidence, and formal complaints that went unacknowledged - proves he was right about that culture.

Why “Best Practice” Letters Don’t Work

The council’s response to resident concerns was to write to businesses requesting they “explore what additional best practicable means could be taken to reduce potential impact.”

But as the council itself acknowledged: “This can only be a request from the Council. Since it is not the statutory regulator in this context the Council cannot require action to be taken."

Translation: We asked them nicely. We have no power to make them comply. Operations will continue unchanged.

When I requested a copy of this letter to see what “best practices” were actually recommended, I received no response.

The letter, if it existed, had no enforcement mechanism. It was administrative theatre - sufficient to claim the council had “acted” on complaints, insufficient to change any actual practices.

What Investigation Should Look Like

I suggested this to the council in November 2022:

“Instead of ‘reacting’ in response to residents' complaints, perhaps try ‘proacting’ and working with us - it could save you a lot of time, effort and money. For example, the Environmental Protection Officer could join the CASH WhatsApp group, or set up a dedicated WhatsApp group for residents to report, investigate and ‘verify’ odours?”

No response. No adoption of this suggestion.

Why not? Because the purpose of investigation isn’t to verify what residents report - it’s to apply methodologies that consistently fail to meet statutory nuisance thresholds while generating paperwork demonstrating the council “took concerns seriously.”

Genuine investigation would:

- Accept resident photographic/video evidence as valid documentation

- Coordinate with residents to target site visits when problems occur

- Treat pattern of complaints as evidence even without direct witnessing

- Apply precautionary principle when fire risk is explicitly identified

- Suspend operations pending safety review when evidence warrants

- Respond to formal complaints within policy timescales

None of this occurred.

The Question We Should Be Asking

So the answer to “Why didn’t anyone from the council check it out?” is:

They did. They conducted a year-long investigation. They made site visits. They reviewed concerns. They coordinated across departments. They generated reports. They denied responsibility. And then they determined that no action was required.

The better question is: Why do investigation methodologies consistently fail to verify harm that residents can document, predict, and experience - until catastrophic failure proves residents were right all along?

That question exposes something more troubling than neglect.

It exposes systems designed to manage complaints rather than address harm.

It exposes regulatory frameworks that prioritise operational continuity over precautionary protection.

It exposes methodologies that require perfect evidence at the perfect moment, while rejecting pattern evidence from residents whose daily lives give them vastly more observation time than occasional site visits.

It exposes jurisdictional confusion that functions as liability shield, with each authority claiming another holds responsibility until harm escalates beyond deniability.

The Accountability Gap

The fire occurred exactly as residents predicted in explicit written warnings submitted 30 months prior, accompanied by photographic evidence, video documentation, and formal complaints.The council conducted a year-long investigation and found no evidence requiring enforcement action.

One of these accounts is accurate. Both cannot be.

Either residents fabricated evidence of problems that didn’t exist, or investigation methodologies are designed to avoid verifying harm that does exist.

The fire proves which account is accurate.

What This Means

The Johnson Street fire should not be investigated as an isolated incident of unknown cause. It should be investigated as the predictable endpoint of regulatory culture that prioritises paperwork over precaution.

The investigation should examine:

- Why year-long daily monitoring failed to verify harm residents documented in three visits

- Why photographic and video evidence was insufficient to trigger enforcement action

- Why explicit fire risk warnings in formal complaints went unacknowledged

- Why “best practice” letters with no enforcement mechanism substitute for operational suspension when evidence warrants

- Why jurisdictional confusion between council and Environment Agency persists across multiple cases

- Why complaint policy breaches occurred when formal escalation was attempted

- Whether investigation methodologies are designed to verify harm or to avoid triggering enforcement thresholds

Any investigation that treats this fire as unforeseeable - when residents literally foresaw it and documented the prediction - will miss the essential truth.

This fire happened not despite investigation, but because of how investigation operates when applied to communities whose warnings are systematically discounted.

The council checked it out. They spent a year checking it out. That’s what makes this worse.

Because it means the fire occurred not through ignorance, but through choice: the choice to conduct investigations in ways that consistently fail to verify harm, to accept jurisdictional confusion as operational framework, to substitute “best practice” letters for enforcement action, and to leave formal complaints unacknowledged until catastrophic failure forces temporary intervention.

They checked it out. They found nothing. And then exactly what residents warned about came true.

That’s not regulatory failure. That’s regulatory function.

The full correspondence documenting this timeline is available through Freedom of Information requests to Ealing Council. Residents deserve to see what “year-long daily investigation” actually produces when applied to explicit warnings that later prove accurate.