A Site That “No One Checked”?

When a commenter asked why “no one from the council checked” Sam’s Recycling before the Johnson Street fire, the short answer is uncomfortable:

The council did check. Repeatedly. For over a year.

And officially, they found nothing.

Yet the risks were documented.

What follows is drawn from Environment Agency inspection reports, enforcement correspondence and Environmental Information Request disclosures obtained in early 2024 by a local resident (anonymised here).

Together, they form a paper trail showing regulatory awareness without proportionate intervention.

The Fire Was Not the Beginning

On 11 January 2026, around 15 tonnes of mixed recycling burned at Sam’s Recycling. Eight fire engines attended. Rail services were disrupted. Smoke spread across surrounding streets.

But the conditions that made that fire possible had been recorded years earlier.

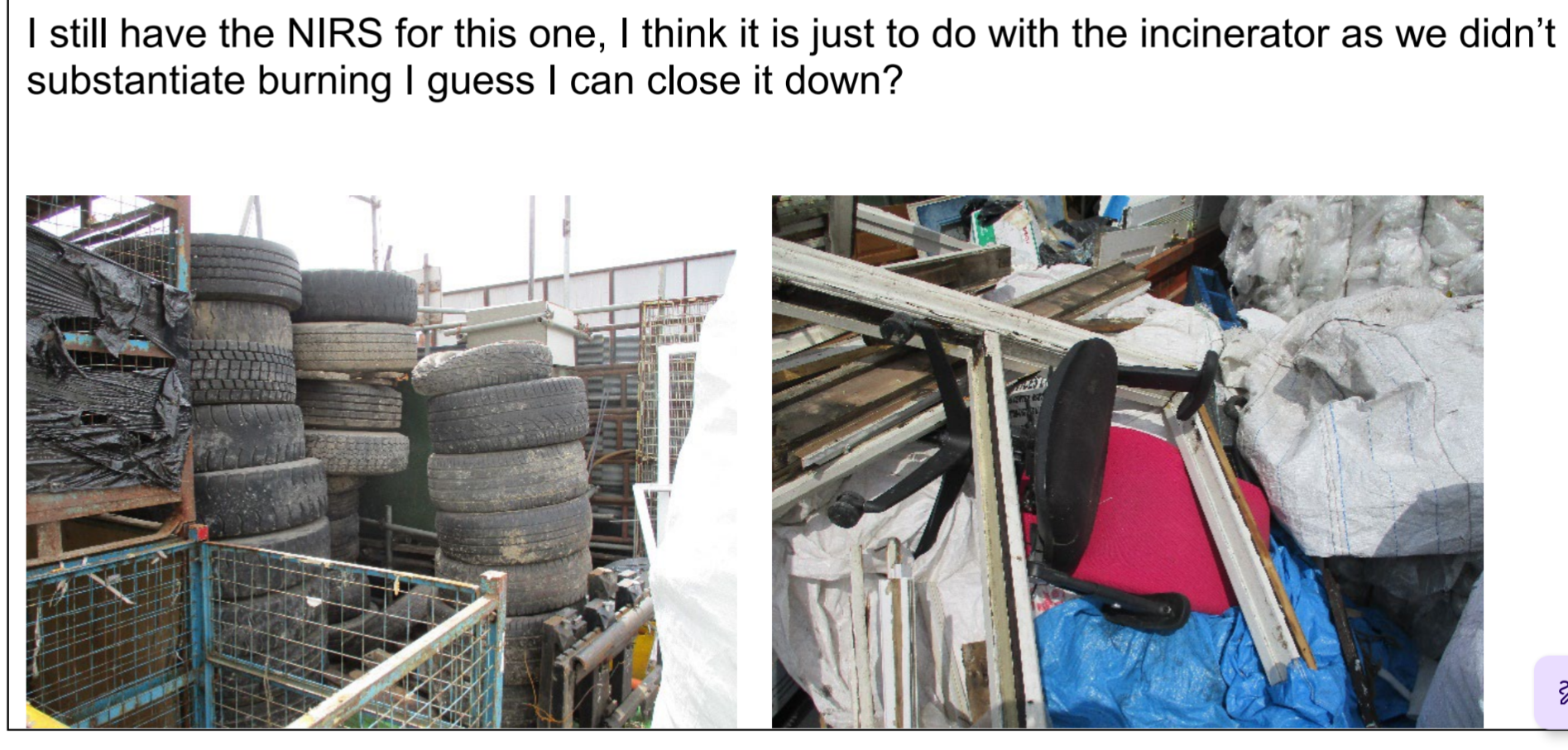

EA inspection notes from November 2022 describe a site already presenting multiple fire and pollution risk factors:

“Waste was stored quite densely in this area of the site, there was no path through the waste. Officers had to climb over waste piles to see the full extent and content of the waste.”

They also recorded:

- Gas canisters and fire extinguishers stored without containment

- uPVC frames, waste wood, baled plastics and mixed packaging stored together

- Tyres stacked approximately ten high

- No drainage observed on either operational area

This was not an invisible problem.

The “Sensitive Receptor” Warning

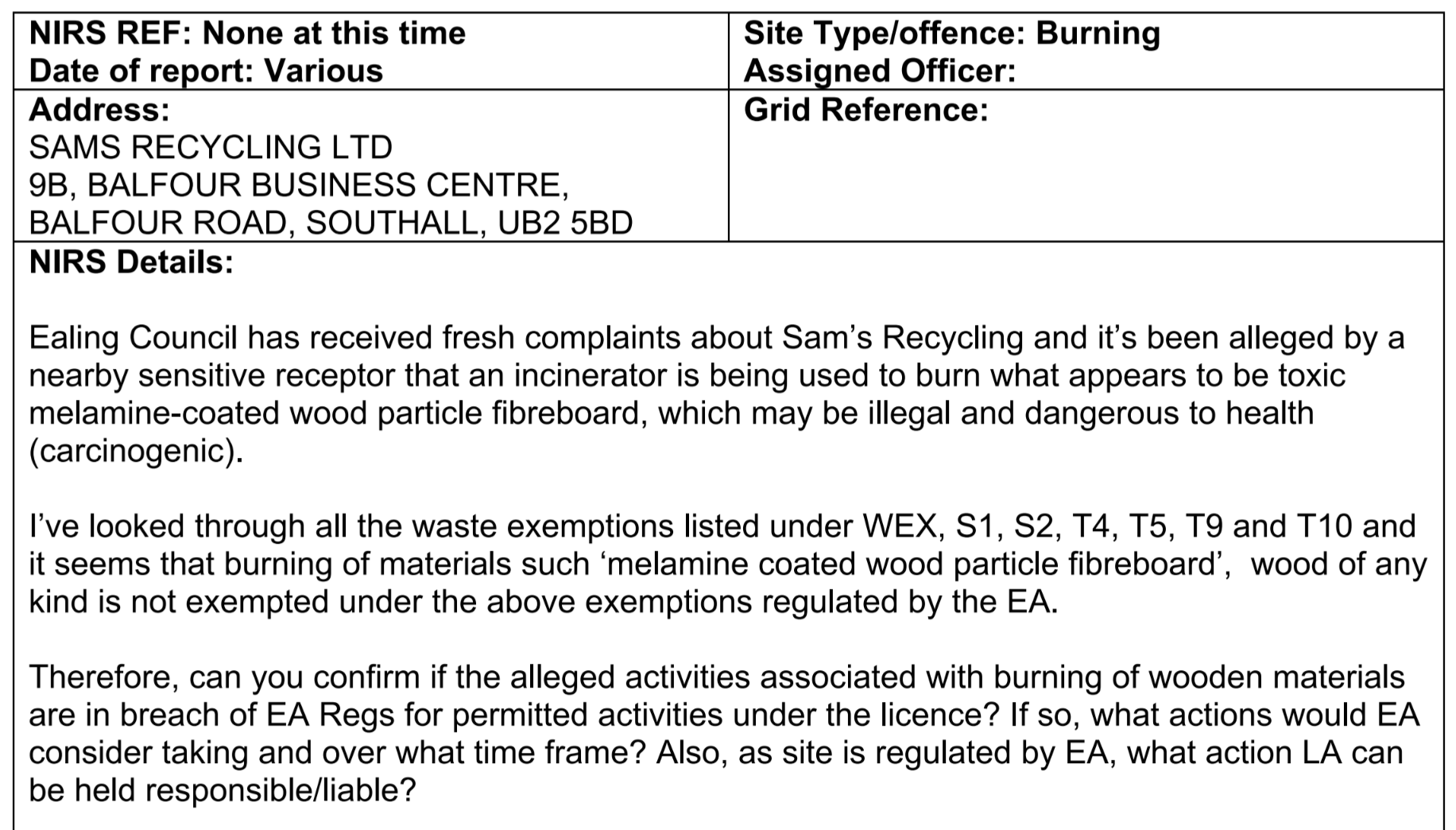

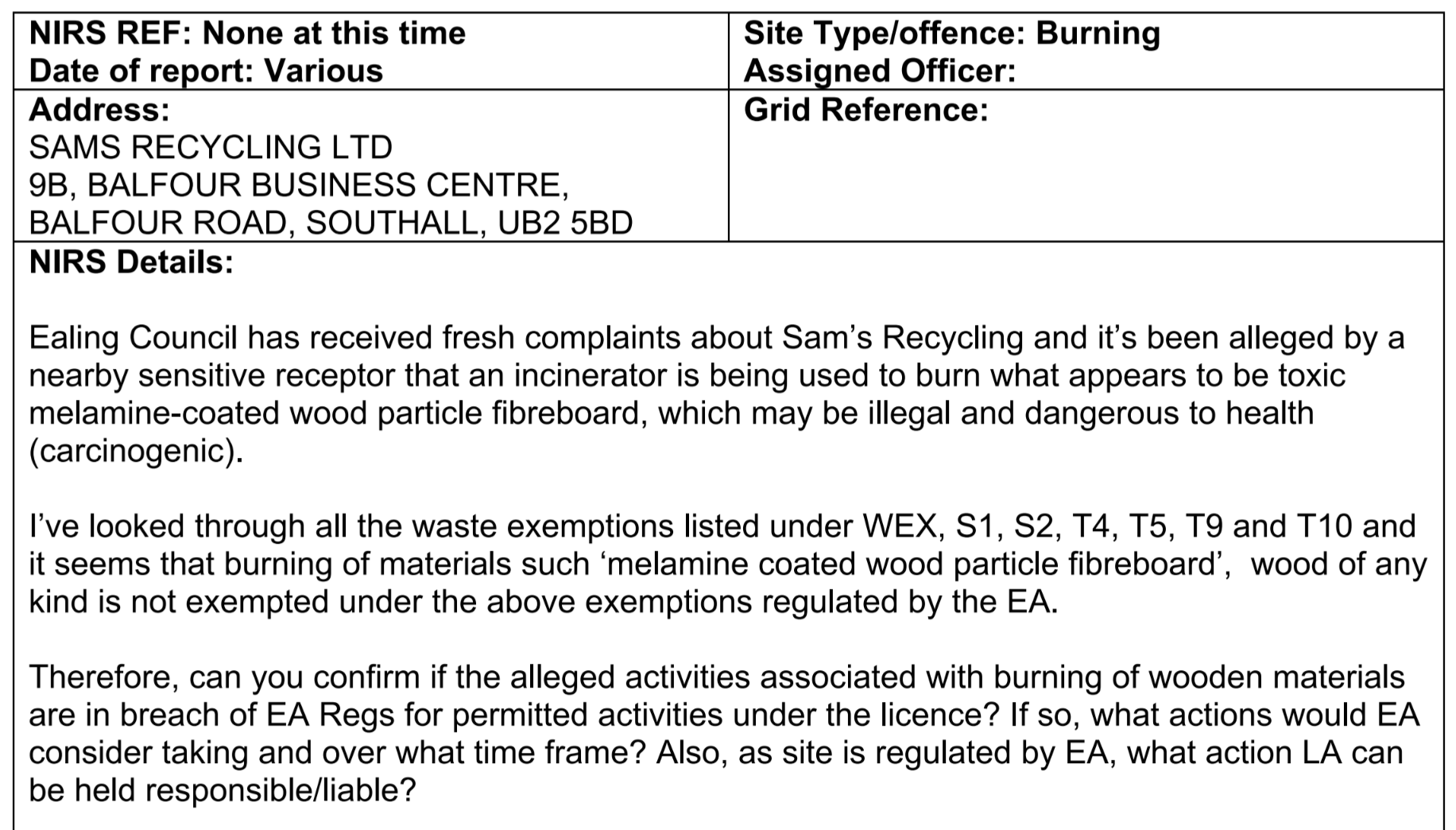

In November 2022, regulators recorded a formal complaint from a nearby resident described in official correspondence as a “sensitive receptor”:

“It’s been alleged by a nearby sensitive receptor that an incinerator is being used to burn what appears to be toxic melamine-coated wood particle fibreboard, which may be illegal and dangerous to health (carcinogenic).”

The operator was explicitly warned:

“Burning waste is an offence under Section 33 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990.”

They were instructed to cease burning immediately.

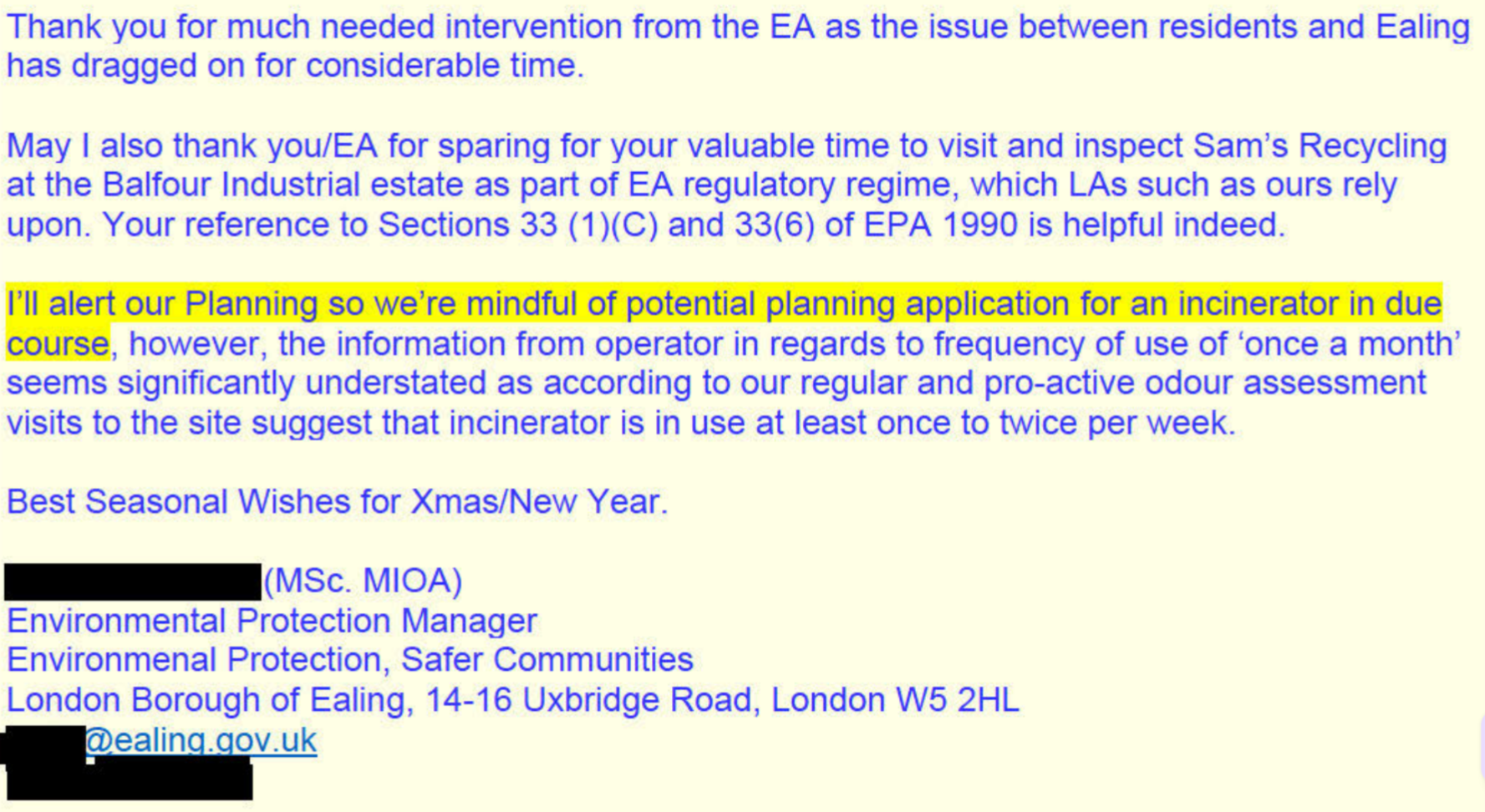

Yet follow-up correspondence shows inspectors believed incinerator use continued:

“Our regular and pro-active odour assessment visits suggest that the incinerator is in use at least once to twice per week.”

Another internal note adds:

“I have no doubt that the frequency given to us was inaccurate.”

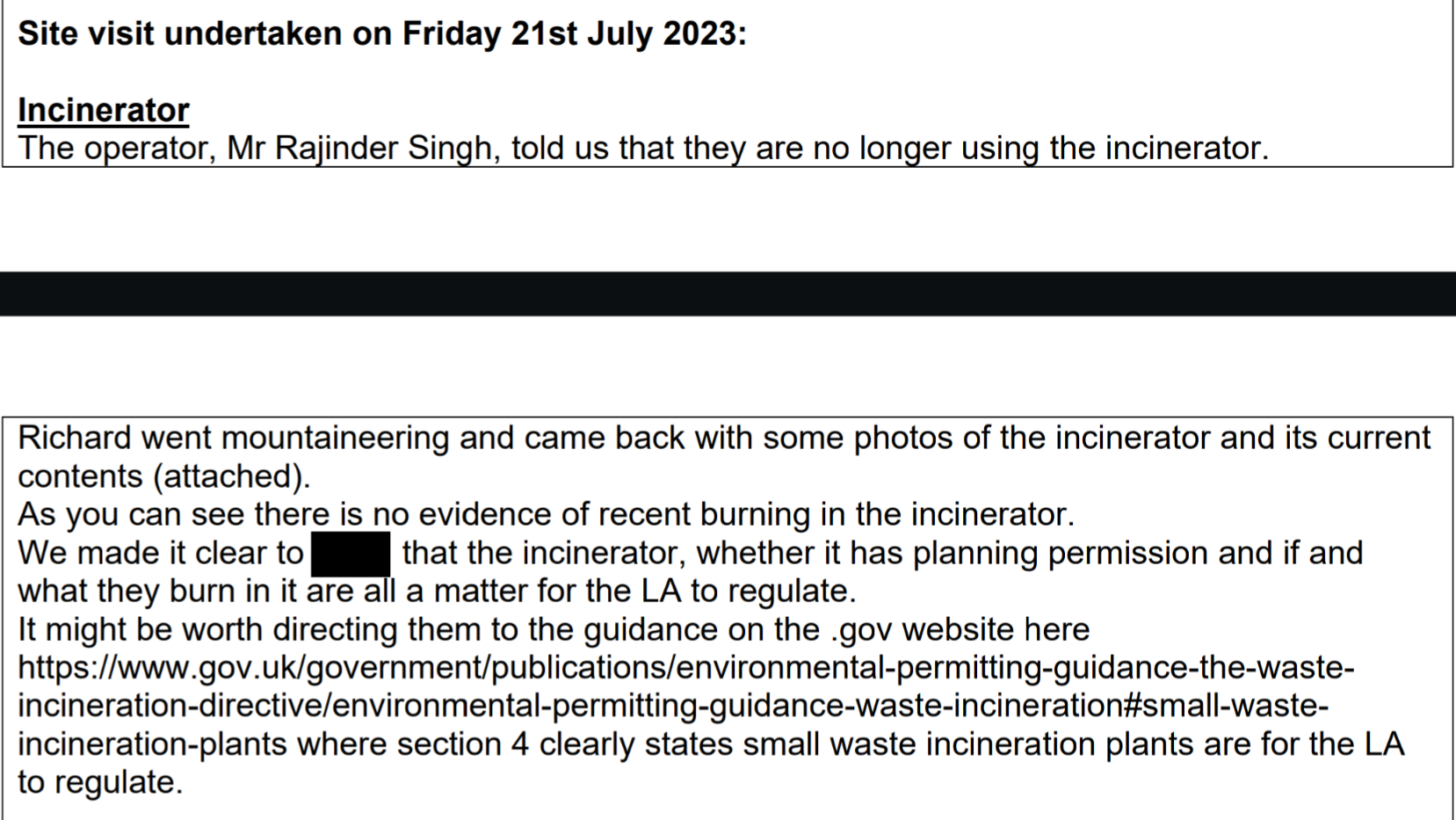

“Mountaineering” Over Waste

By July 2023, inspectors were still documenting extreme site conditions.

One visit record states:

“Richard went mountaineering and came back with some photos of the incinerator and its current contents.”

This is not journalistic exaggeration. It is the agency’s own language.

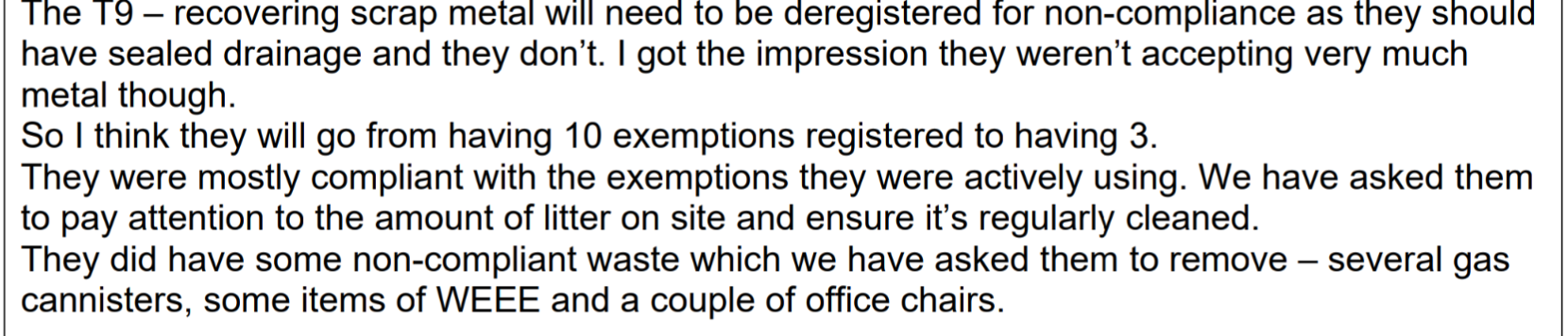

The same inspection recorded:

- Several gas canisters on site

- Non-permitted electrical waste

- Office equipment and furniture stored near the incinerator

- Poor housekeeping and litter control

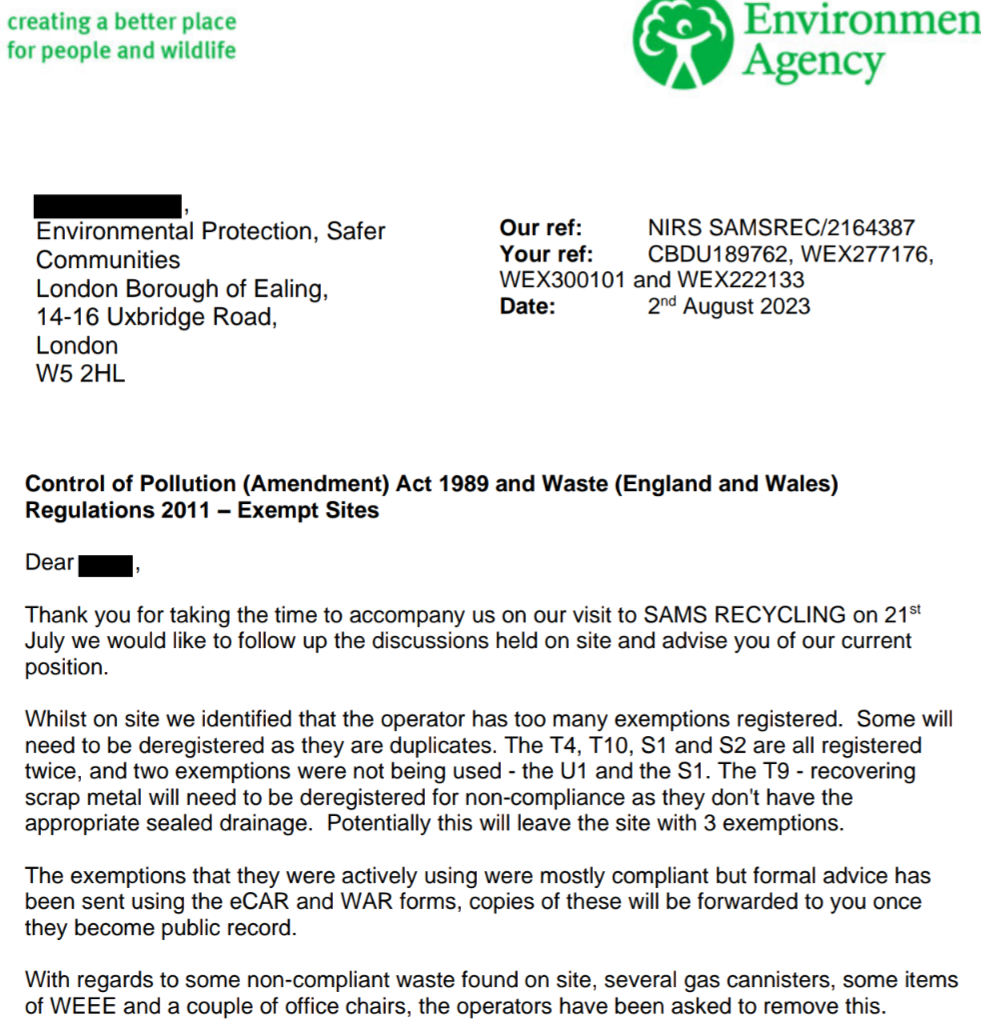

Enforcement — But Only Selectively

In August 2023, the EA finally issued enforcement instructions — but only relating to specific non-permitted waste streams (gas canisters, WEEE items, photocopiers, chairs).

The formal action required removal of these items by 14 August 2023.

Yet at the same time, inspectors concluded:

“The S2 exemption is in use… The site are in compliance with the limits, conditions and waste types permitted.”

This meant that large-scale external storage of cardboard and paper bales — a known fire risk — was treated as compliant, despite earlier observations of excessive stacking heights and dense storage conditions.

What The Site Looked Like Last Week

I visited the site in January 2026, days after the fire.

What follows is not historical archive material. This is post-fire reality.

Entrance to the Johnson Street recycling site, January 2026. Standing water and pooled runoff remain visible a week after the fire. EA inspections previously recorded that “no drainage was seen on either area of the site”.

Fire-damaged structural remains visible from the entrance to the industrial estate. Sections of collapsed roofing and exposed framework remain in place.

Large mixed waste stockpile occupying the central yard. EA inspection records previously noted that waste was stored so densely officers “had to climb over waste piles” to inspect the site.

What The Operator Told Me

During my visit I spoke briefly with a man who claimed to be the owner. He refused to give his name.

He described the fire as:

“An unfortunate accident. These things happen.”

He referenced the Charles House Bridge Road warehouse fire and suggested this was comparable.

When I raised the question of enforcement failures and long-documented hazards, he rejected that framing and instead pointed to neighbouring business units, arguing that others nearby were in similar or worse condition.

He speculated that the fire may have been caused by a discarded e-cigarette, but admitted he had no evidence to support this claim.

He also stated that the fire had cost his business “over half a million pounds” in lost trade.

The Pattern That Emerges

Across the EA documents, several themes repeat:

- Hazards identified early

- Unsafe storage documented

- Incineration activity suspected to continue

- Complaints escalated

- Partial enforcement applied

- Core fire-risk practices allowed to persist

This is not regulatory absence.

It is regulatory containment.

Not An Accident — A System Failure

The Johnson Street fire did not occur in isolation.

It occurred at a site where regulators had:

- Recorded combustible storage density

- Documented blocked access routes

- Logged repeated burning complaints

- Observed dangerous mixed waste storage

- Issued selective enforcement without broader operational shutdown

Calling this an “unfortunate accident” erases the paper trail.

The real question is not how the fire started.

It is why the conditions that made it likely were allowed to continue.

What Happens Next?

Investigating authorities have said the cause of the fire is “not yet known”.

But the regulatory context is known.

The paper trail exists. The inspections happened. The warnings were issued.

And the site still burned.