With council elections less than three months away, Ealing Council is busy using “Ealing Council’s magazine for residents” to promote news of Ealing Labour’s local “achievements” in an effort to persuade voters that, despite national Labour’s dismal regurgitation of failed and cruel Tory government austerity policies and shameless political scandals going right to the heart of the UK establishment, Peter Mason’s Ealing Labour are still “on your side”.

Yesterday I looked at fly-tipping data after the council announced in its draft 2026-27 budget yet another “crackdown” to solve an expensive problem that appears to be largely of its own making.

A week later the council trumpeted its “success” in securing £27m from developers to create much-needed infrastructure to cope with the circa 100,000 new residents expected to live in the more than 120 new tower blocks approved for development across the borough.

Graphic from Stop The Towers campaign

Section 106 money - described as a “developer tax” by Ealing Council - is paid by developers as a form of mitigation for being allowed to build schemes that would otherwise place extra strain on local infrastructure.

The national Planning Portal defines S106 thus:

“Planning obligations, also known as Section 106 agreements (based on that section of The 1990 Town & Country Planning Act) are private agreements made between local authorities and developers and can be attached to a planning permission to make acceptable development which would otherwise be unacceptable in planning terms.”

In plain English, that can sound less like mitigation and more like a system where developments become acceptable once the right cheque is written.

In Southall, they’re known euphemistically as “brown envelopes”.

In theory, it works like this:

- A developer gets planning permission.

- The council negotiates a Section 106 agreement.

- The developer pays contributions for things like:

- Schools

- GP surgeries

- Parks

- Roads

- Air quality

- Training and employment

The idea is simple:

if you add thousands of new residents, you help pay for the infrastructure they’ll need.

In practice, the numbers for Southall tell a more complicated story.

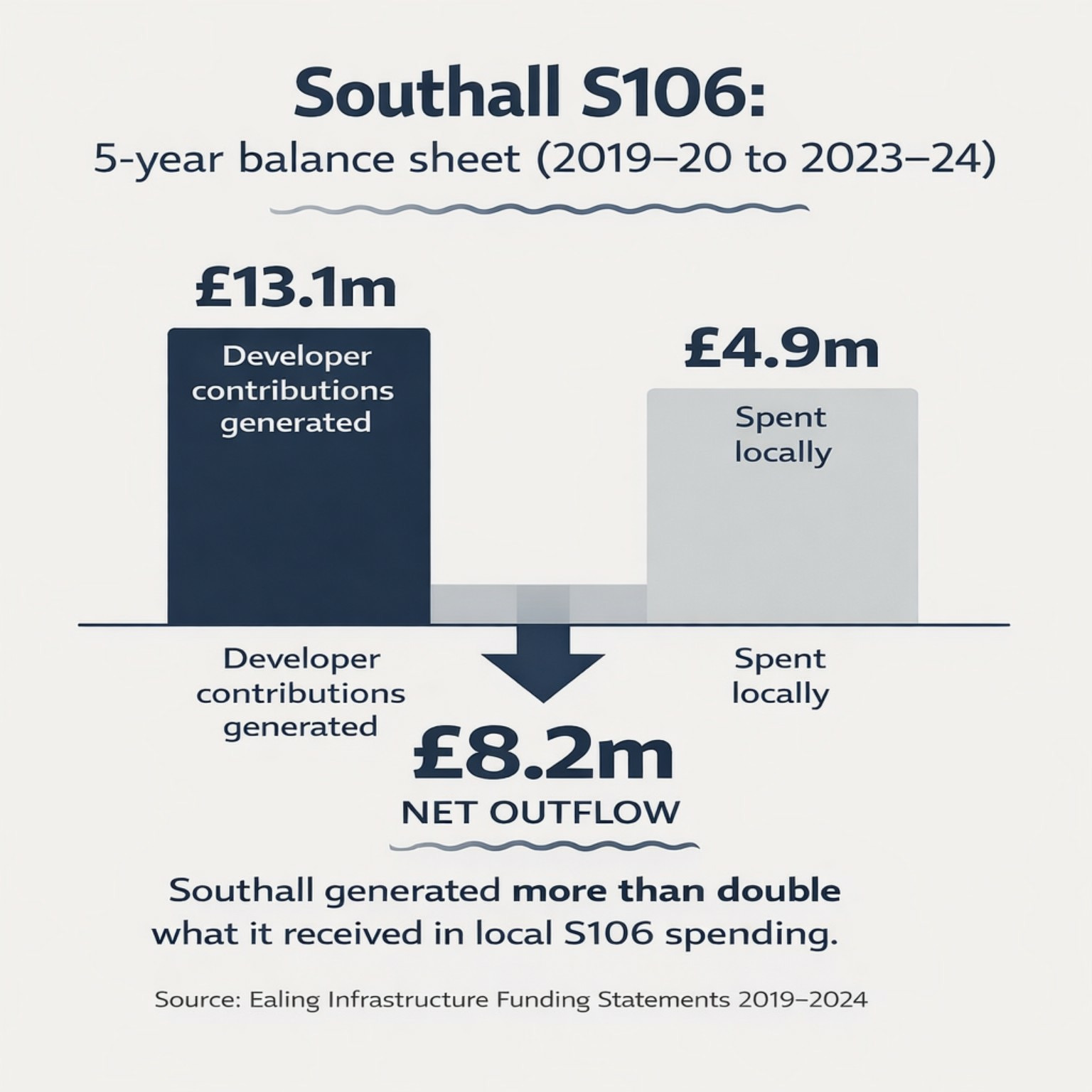

Southall’s Section 106 balance sheet (2019–2024)

Using Ealing Council’s own Infrastructure Funding Statements, we can track how much S106 money Southall generated and how much was actually spent there.

Five-year totals

2019–20 to 2023–24:

| Category | Amount |

|---|---|

| S106 income from Southall developments | £13.1 million |

| S106 spending in Southall | £4.9 million |

| Net position | +£8.2 million |

Over five years, Southall generated at least £13.1m in developer contributions but received £4.9m in spending—a net outflow of £8.2m.

The spike year: 2022–23

| Year | Southall income | Southall spend |

|---|---|---|

| 2022–23 | £7.15m | £0.78m |

So in that one year alone:

Southall generated over £7 million in developer contributions, but less than £800,000 was spent locally.

That’s a net outflow of £6.3 million in a single year.

Where the money actually went

When you look at the project lists, most of the Southall spending falls into a few categories.

The biggest single project

Southall Market affordable housing

- Around £899,000 in S106 spending

- The largest single Southall project across the five years

This scheme:

- Stalled in 2023

- Is now at risk of demolition

So a large share of the town’s S106 spending is tied up in a project that may never deliver homes.

The next largest item

Southall foot and cycle bridge

- Around £225,000 in S106 funding

After that, most projects are much smaller:

- Outdoor gyms

- Running tracks

- Tree planting

- Small park upgrades

- Air-quality monitoring

- Training schemes

- Minor highways works

Many are in the £5,000–£100,000 range.

Big allocations that never materialised

Some of the largest Southall allocations were not actually spent.

For example:

- Southall health hub: £1.81m allocated (2022–23), unspent at year end

- Public realm works: £328k allocated, unspent

So even where large sums were earmarked, the infrastructure often wasn’t delivered.

Southall vs Acton: the growth areas compared

Over four comparable years (2020–21 to 2023–24):

| Town | Total income | Total spend | Net position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southall | £12.4m | £4.9m | +£7.5m |

| Acton | £15.6m | £6.1m | +£9.5m |

Both of the borough’s biggest growth areas:

- Generated huge S106 income

- Received far less in spending than they produced

Southall Gasworks (aka The Green Quarter): a flagship scheme

The council’s own FOI response gives a rare scheme-specific total.

Southall Gasworks (aka Green Quarter) S106 (2015–2022)

Total received from the development:

£1,749,584

For one of the largest housing developments in West London, delivering thousands of homes, that’s:

Under £2 million in S106 contributions over seven years.

What that money paid for

| Contribution | Amount |

|---|---|

| Education | £840,363 |

| Swimming pool contribution | £188,558 |

| Employment & training | £256,955 |

| Air quality | £129,226 |

| Highways and bus lane | £146,000 |

| Signage & CPZ review | £138,482 |

| Contaminated land officer | £50,000 |

Total: £1.75m

But:

- There is no new swimming pool serving the development.

- The education funding is not tied to a clearly visible new Southall school.

The council’s £27 million claim

Recently, the council said:

“£27 million has been invested in our borough since 2022, paid for by developers.”

But the official figures show:

- 2022–23 S106 spend: £3.9m

- 2023–24 S106 spend: £11.5m

Total spent since 2022:

- £15.4 million

So the £27m figure appears to include allocations or commitments, not just actual spending.

Southall’s share since 2022

| Year | Southall income | Southall spend |

|---|---|---|

| 2022–23 | £7.15m | £0.78m |

| 2023–24 | £0.83m | £1.49m |

Two-year totals:

- Southall income: £8.0m

- Southall spend: £2.3m

Since 2022, Southall has generated almost £8m in developer contributions but received only about £2.3m in spending.

The bottom line

Across five years:

- Southall generated at least £13.1 million in S106 income.

- Only £4.9 million was spent in the town.

- Net outflow: £8.2 million.

And much of that spending was:

- One stalled housing project

- One foot and cycle bridge

- A scattering of smaller schemes

Meanwhile, the biggest allocations - like the Southall health hub - remain undelivered.

The £11.8 million bridge that was never built

One of the biggest infrastructure promises tied to Southall’s redevelopment was the widening of South Road bridge, the main road over the railway near the station.

This was not a minor improvement.

It was a core mitigation project secured through a Section 106 agreement on the former gasworks site — now the Green Quarter.

According to the council’s own report:

“The widening of the South Road Bridge is a S106 planning obligation on the Green Quarter site (formerly Southall Gas Works) and was secured in 2010.”

The logic was simple:

Thousands of new homes were planned around the station.

Traffic levels were expected to rise sharply.

The bridge widening would help reduce congestion and improve access.

The council report explained:

“With the considerable volume of new housing currently being developed in Southall… additional measures and infrastructure is required to reduce traffic congestion… South Road bridge widening has been long proposed as a measure to help reduce the congestion.”

What went wrong

Originally, around £11.875 million was available for the project through S106 and housing zone funding.

But costs spiralled.

By 2021: The estimated construction cost had risen to £29.6 million.

By 2022: The council had already spent £2.58 million on feasibility studies, design and pre-construction work.

But concluded the project was no longer viable.

The report recommended:

“The Council should not commission any further technical or design work on this project… and close the project.”

The outcome

| Item | Status |

|---|---|

| S106 obligation secured | 2010 |

| Infrastructure promised | South Road bridge widening |

| Budget available | £11.875m |

| Spent on design/pre-construction | £2.58m |

| Final estimated cost | £29.6m |

| Outcome | Project abandoned |

The housing went ahead.

The bridge widening never did.

This is a textbook example of how Section 106 is supposed to work in theory - major development is approved because infrastructure will follow - and how it can fail in practice when the promised mitigation is never delivered.

The council says the developer tax is working.

The figures suggest something else: millions flowing in, much less flowing back, and a bridge that was meant to arrive before Crossrail that never came at all.

With the elections just weeks away, Southall’s voters may want to look past the slogans and ask a very old-fashioned question: where did the money go?