You’ve got to hand it to Peter Mason.

Every four years he manages to regenerate, reinvent and transform himself and Ealing Labour into a new and improved version of reality.

He has a creative imagination. His ambition is unbridled. He is resilient and resourceful. Nothing, it seems, can stop him recycling ever more of the same old rubbish manifesto promises while simultaneously presenting them to the public as successful achievements we should want more of.

Of course, it would be unfair to pretend Mason is alone among politicians in this kind of performance. We’ve seen it all before. And that’s really the crux of the problem.

As the loyal leader of the local incarnation of the “Party for (Short) Change,” he is the continuity candidate — the one person most likely to ensure that things stay exactly as they are. Or get even worse.

Let’s take a closer look at the record.

By his own admission just two weeks ago, Ealing has had sixteen years of cuts to frontline services under Labour control.

Julian Bell was leader until 2021, but it was Mason who coordinated the 2018 manifesto, and it’s clear he was heavily involved throughout all sixteen years.

It is hard to believe the 2022 manifesto, under his fledgling leadership, was written by anyone else. His fingerprints are all over it.

The priorities themselves have remained broadly the same, even if the labels have been given makeovers.

In 2018, Mason was cabinet lead for Housing, Planning and Transformation, while colleagues held traditional portfolios for:

- Finance and Leisure

- Business and Community Services

- Health and Adult Services

- Environment and Highways

- Schools and Children’s Services

By 2021, and with an open and transparent promise to uphold the most basic Nolan Principles of public life, the same machinery had been repackaged under a new set of slogan-based titles:

- Genuinely Affordable Homes

- Decent Living Incomes

- A Fairer Start

- Healthy Lives

- Climate Action

- Good Growth

- Inclusive Economy

- Thriving Communities

- Tackling Inequality

- Tackling Crime and Antisocial Behaviour

There were further cabinet reshuffles, deckchair rearrangements, and revolving door entrances and exits at Perceval House - the seat of local democracy in Ealing - in 2022 and 2024.

The top table now looks like this, and there’s even some detailed descriptions about who is responsible for what.

Here’s a rough guide to who does what in Peter Mason’s brave new world of local democracy:

Cabinet portfolios: then and now

| 2018 functional role | 2021–2026 slogan title | Core services underneath |

|---|---|---|

| Schools & Children’s Services | A Fairer Start | Children’s services, early years, education, SEND |

| Health & Adult Services | Healthy Lives | Adult social care, public health, disability services |

| Housing, Planning & Transformation | Genuinely Affordable Homes / Good Growth | Council housing, planning, regeneration, development |

| Finance & Leisure | Inclusive Economy / parts of Thriving Communities | Finance, procurement, culture, leisure, economic strategy |

| Business & Community Services | Thriving Communities | Libraries, community centres, voluntary sector, neighbourhood services |

| Environment & Highways | Climate Action | Waste, recycling, transport, highways, air quality, green policies |

| Employment / regeneration functions | Decent Living Incomes | Skills, employment, apprenticeships, local economy |

| Cross-departmental social policy | Tackling Inequality | Housing need, welfare support, public health, children’s services, community development |

| Community safety and enforcement | Tackling Crime and Antisocial Behaviour | ASB teams, enforcement, CCTV, regulatory services, police partnerships |

Instead of departments and delivery, the focus had shifted to something else: a story.

And it’s a very attractive story.

Who doesn’t want genuinely affordable homes? Who would argue against decent living incomes? Who could oppose a fairer start or healthy lives?

But if you wanted to know who was actually responsible for delivering those promises — and how much had really been achieved — the answers were often harder to find.

While Mason crafted an elaborate tale out of aspirational slogans, and promised ever greater numbers of homes, parks, swimming pools, sports pitches, nature reserves, school streets, living wages - and even beavers - a different question lingered in the background:

How does the beautiful story match up to the rather grimmer reality?

The easiest place to look for an answer is the manifestos themselves. Unlike the cabinet titles, the manifestos came with numbers attached. Clear targets and deadlines. Promises that were supposed to be measurable.

And both the 2018 and 2022 manifestos were written under the same leadership, by the same man. Same party. Same council. Same housing crisis.

So they can be compared directly. Not as political ideology, or as spin, but as numbers. And once you put those numbers side by side, the story starts to look very different.

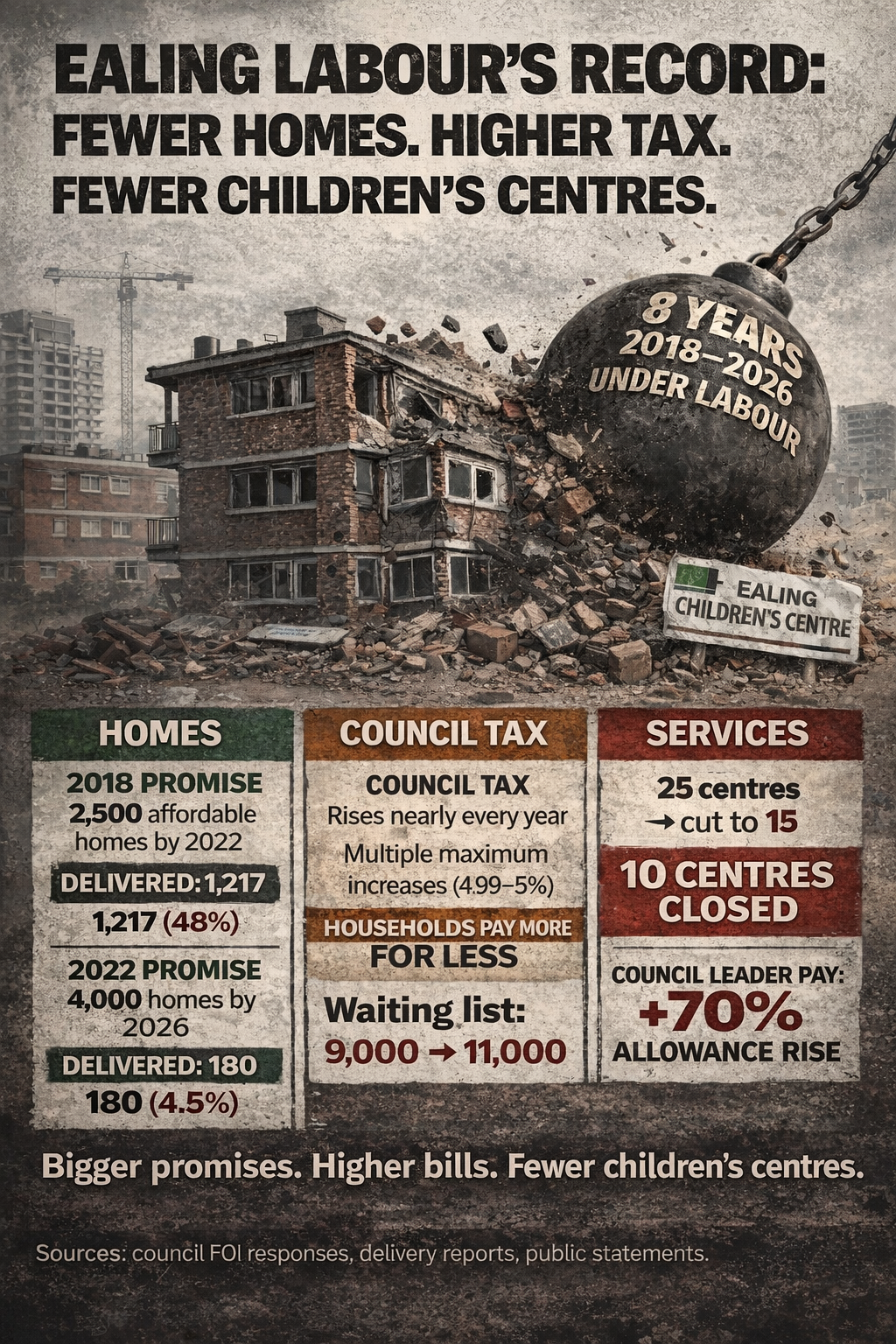

From 2,500 to 4,000 to 180

What changed between Ealing Labour’s 2018 and 2022 manifestos?

In both the 2018 and 2022 local elections, Ealing Labour asked voters for a fresh mandate based on a new manifesto. Both documents were ostensibly written by Peter Mason, and both were built around big, measurable promises — especially on housing.

But when the two manifestos are placed side by side, a pattern emerges.

The targets got bigger. The delivery got blurrier.

The central promise: affordable homes

In 2018, the commitment was simple:

2,500 genuinely affordable homes by 2022

A number. A type of home. A deadline.

It was one of the centrepieces of the manifesto — presented as one of the most ambitious council housebuilding programmes in London.

Four years later, the new manifesto raised the stakes:

4,000 genuinely affordable homes across the borough

A bigger number. A new deadline. A fresh promise. But what happened to the original one?

2022: the council’s own figures

By early 2022, as the 2,500-home deadline approached, the council’s internal performance dashboard showed the housing target marked:

RED

The number displayed:

1,277 homes completed or on site

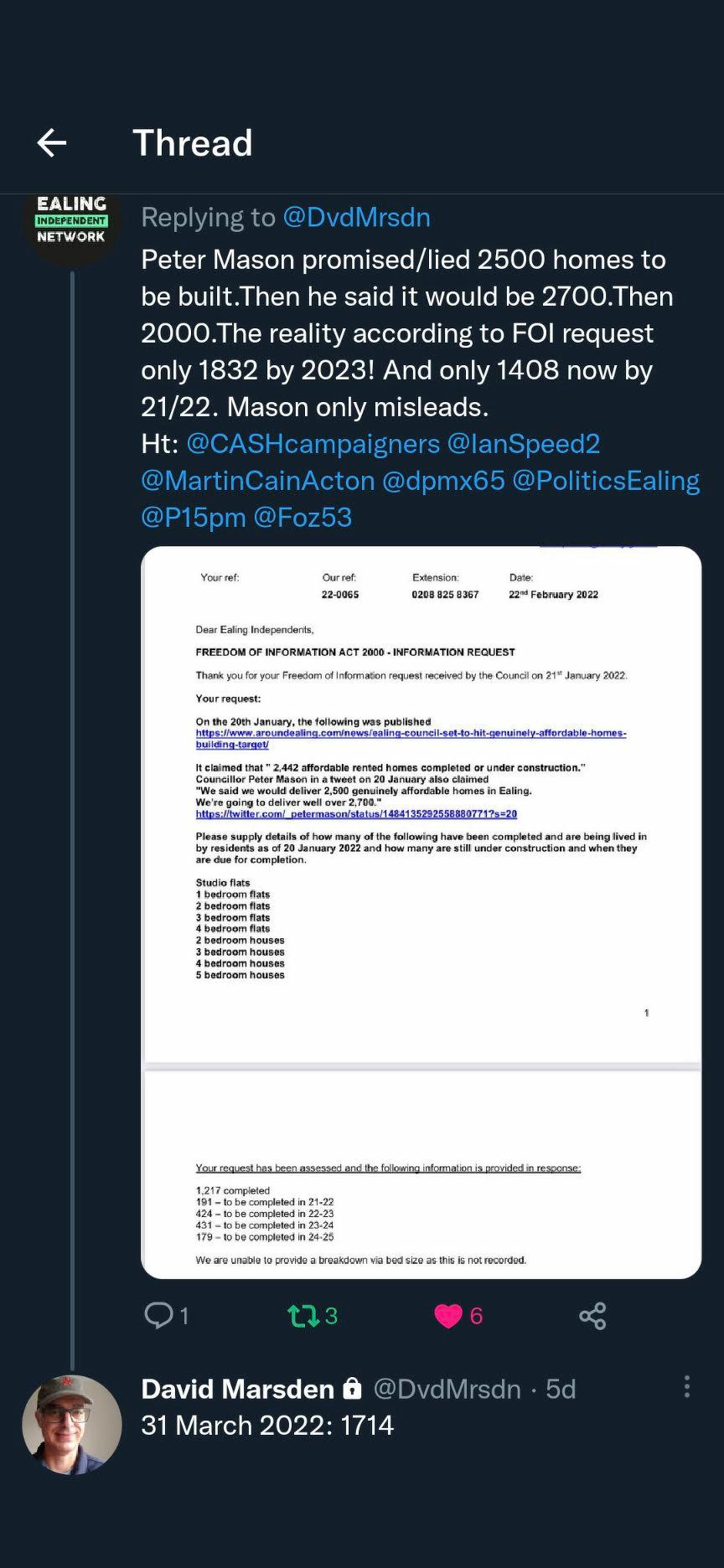

A Freedom of Information response to Ealing Independents gave a clearer breakdown:

- 1,217 homes completed and occupied

- The rest still under construction

- Some not due until 2024 or 2025

So by the actual 2022 deadline:

- Fewer than half the promised homes had been completed

- Hundreds existed only as construction sites

- Others were still years away

The moving numbers

Over the life of the programme, the public totals shifted repeatedly:

- 898 homes

- 1,355 homes

- 723 homes

- 1,965 homes

- 2,442 homes

- 2,700 homes

Different announcements. Different definitions. Different counting methods. Sometimes the figures included homes:

- Not completed

- Not occupied

- Or not yet built at all

In some cases, a “new home” meant:

A hole in the ground with foundations poured.

The 2,700 claim

During the 2022 election campaign, Labour publicly claimed:

“Over the last four years, we’ve built 2,700 genuinely affordable homes.”

But at the same time:

The council’s own dashboard showed around 1,217 completed.

The target was marked RED.

The higher 2,700 figure appears to have included homes still under construction, in the wider development planning pipeline, and possibly other programmes beyond the core council build.

In other words, it was a number that was pure “political theatre”, and absolutely not a number that bore any relation to any lived in reality.

The £100 million question

In 2018, the council received a major grant from the Greater London Authority:

- Around £100 million in funding

- A target of 1,138 new affordable homes

But by early 2026 just 180 of those homes had been completed - about 16% of the target.

According to a Freedom of Information response, £71.9 million had already been spent and work had started on 836 homes. But only a small fraction were actually finished.

So even within the programmes underpinning the manifesto promises, delivery lagged far behind the headlines.

Despite the huge number of new developments across the borough, including over twenty tall towers, and housing potentially over 100,000 people, the proportion of genuinely affordable homes is actually tiny.

Reality doesn’t match fantasy.

2022: a bigger promise

Instead of a clear public reckoning with the 2,500-home target, the 2022 manifesto announced a new, bigger and better promise:

4,000 genuinely affordable homes

But without a single, consolidated figure showing how many of the original 2,500 had actually been delivered, or how many families had moved in, or what the real baseline was.

2024–25: still “contributing”

By 2024, the council’s own delivery plan still listed the same commitment, but the document itself showed something that is, perhaps, revealing. It said the council would:

“Contribute to delivery of 4,000 new genuinely affordable homes”

Not deliver or complete or achieve, but contribute. The 4,000 figure was still a target. Still a work in progress.

2025: target off track

A 2025 scrutiny report confirmed what the delivery plan implied.

The programme was supposed to deliver 4,000 genuinely affordable housing starts by 2026.

But the report also stated the target was off track. It was now expected to reach around 3,000 starts, or 75% of the target. A shortfall of 1,000 homes.

The housing reality behind the manifesto promises

The manifesto comparisons show a simple pattern:

2018: promise 2,500 homes. Deliver around half.

2022: promise 4,000 homes. 2025: target off track by 1,000.

But the manifesto numbers only tell part of the story. Because over the same period, two other housing trends were unfolding.

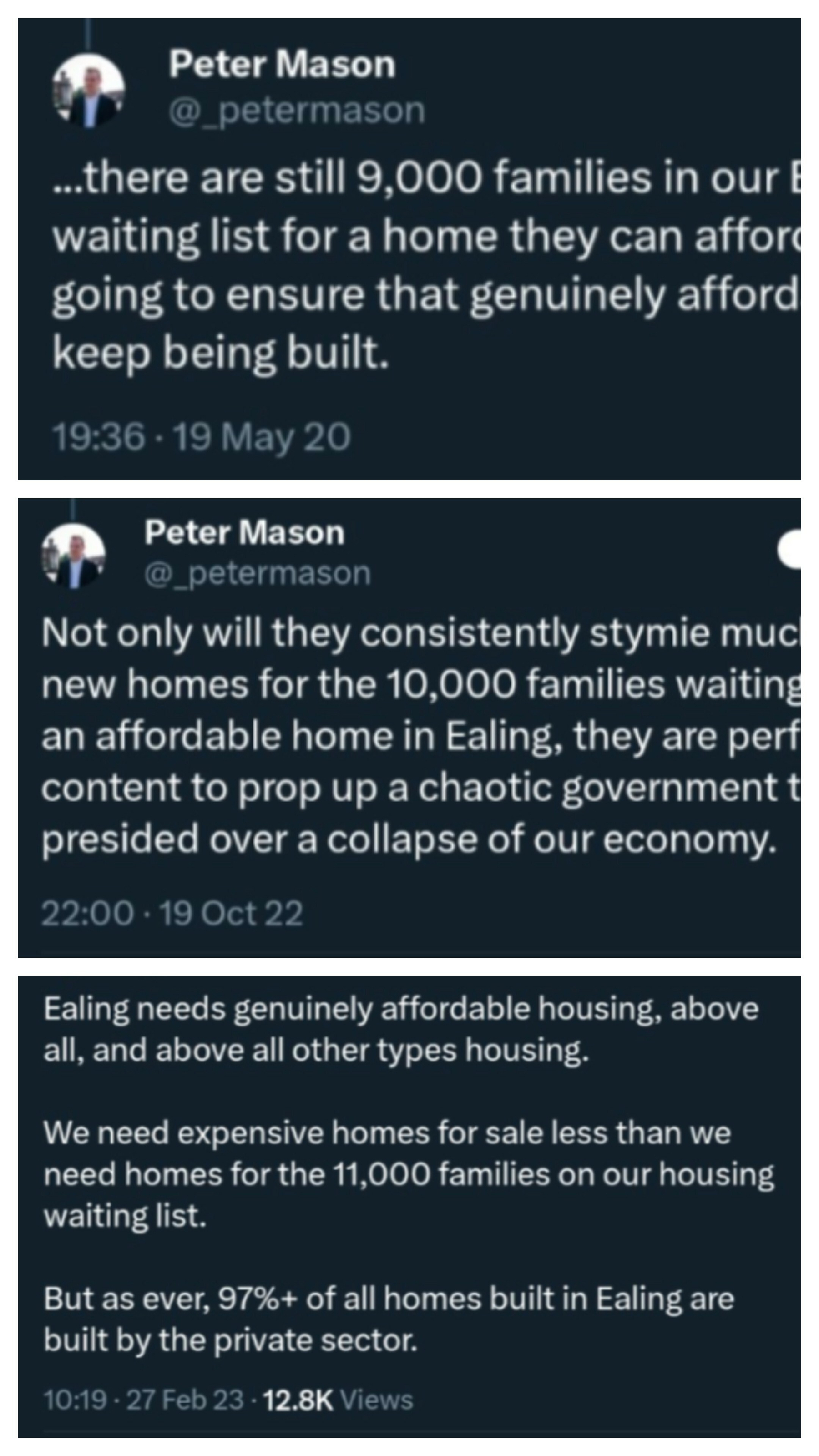

The waiting list that kept growing

Across public statements, the housing waiting list figures moved steadily upward:

Around 9,000 families. Then 10,000. Then 11,000.

Then the official number suddenly dropped.

Today, the council says there are: around 7,500 “live applications”.

At first glance, it looks like progress. But the reason was not a wave of new homes.

The register was tightened

In September 2023, the council introduced a new allocations policy. Under the new system all Band D applicants were removed from the register. Band D was the lowest-priority group. It included thousands of households in housing need. Those families were not rehoused. They were simply no longer counted.

Via a private communication from a reliable source, I was informed that councillors were told:

Currently there are over 12,000 applications on the Housing Register, and this grows by over 100 additional applications per month.

So the waiting list dropped:

From around 12,000 families to about 7,500 applications with the stroke of a pen. Not because homes were built or delivered, but because the list was redefined.

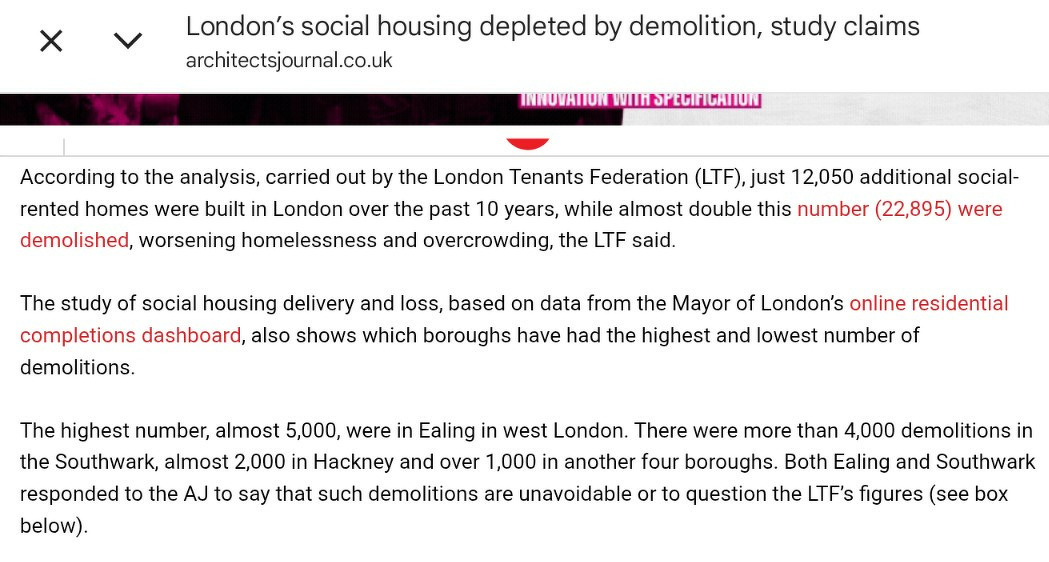

The demolition factor

At the same time, another trend was taking place. According to analysis by the London Tenants Federation:

- 12,050 social-rent homes were built in London over ten years

- 22,895 were demolished

Nearly twice as many homes were lost as gained.

And the borough with the highest number of demolitions?

Ealing.

The study found almost 5,000 social homes demolished in the borough. Many were cleared as part of regeneration schemes, where older social-rent homes were demolished, replacement homes were built later, and often at higher “affordable rent” levels rather than at “social rent” levels.

The long view: 9,000 families, then and now

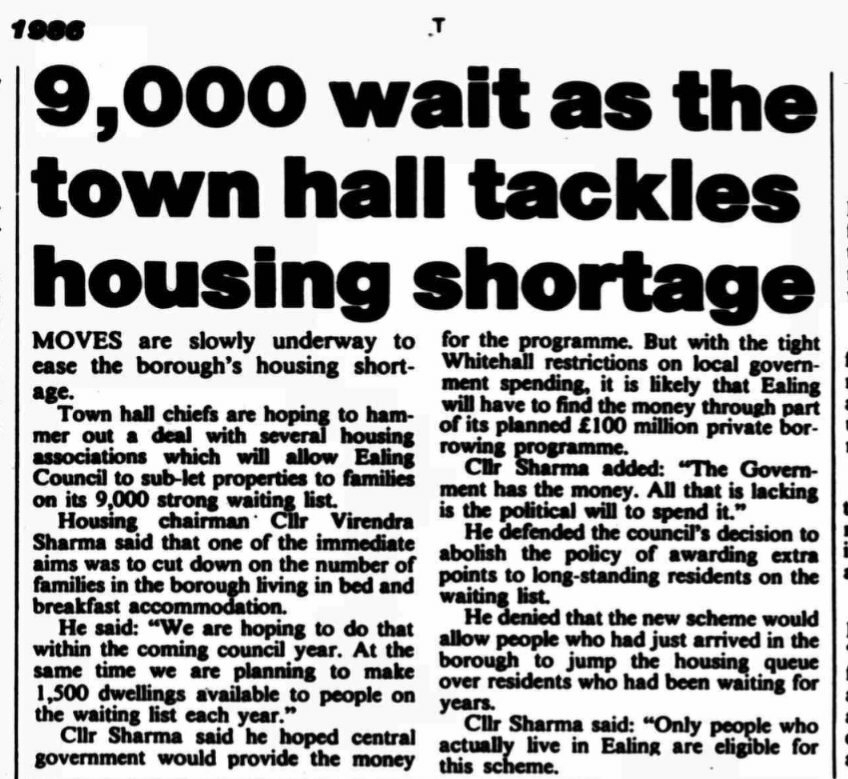

The waiting list has been high for decades. A local newspaper report from 1996 recorded 9,000 families on the waiting list.

Nearly thirty years later, the number had risen above 12,000. The later drop to 7,500 came only after thousands were removed from the register.

So by the early 2020s, the waiting list was higher than it had been in the mid-1990s.

The same argument, thirty years apart

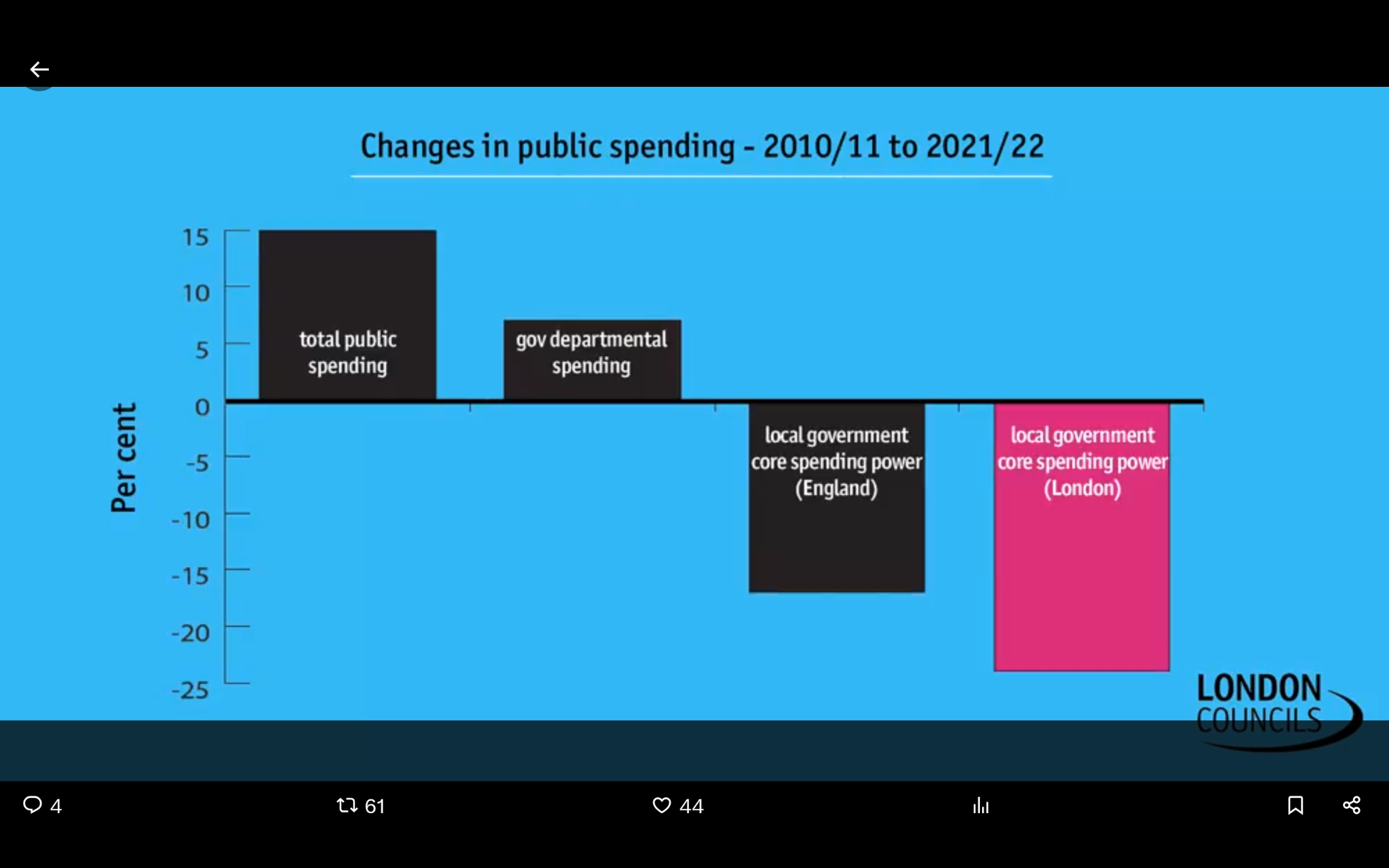

When challenged about the waiting list, council leaders point to funding cuts.

In 2021, London Councils said boroughs had seen a 25% real-terms fall in core spending power since 2010. At the same time, Ealing claimed its direct government grant had been cut by 64%. Both figures can be technically correct. They measure different things. But the deeper pattern is harder to ignore.

Back in 1996, councillors were already saying:

“The Government has the money. All that is lacking is the political will to spend it.”

They blamed Whitehall (central government) spending restrictions. Nearly thirty years later, the waiting list is still at similar levels, and the same arguments are still being made.

Climate: bigger numbers, similar story

The 2018 manifesto spoke in broad ambitions about carbon neutrality, cleaner air (!), more trees, active travel and green spaces.

By 2022, the targets were far more specific:

- 50,000 new trees

- 10 new parks

- 800,000 m² of rewilded land

- 2,000 EV charging points

- 50 School Streets

- Retrofit 750 homes

Some progress has been claimed, with around 50 School Streets delivered, 1,000+ EV chargers installed and more than 40,000 new trees planted.

But for several targets - new parks, rewilding, retrofit numbers, tree canopy targets - there appears to be no clear public scorecard.

Jobs, apprenticeships, and the missing scoreboard

In 2018, economic promises were broad: support local businesses, attract new industries, expand apprenticeships.

By 2022, the targets were precise:

- 10,000 new jobs

- 2,000 apprenticeships

- 12,000 training outcomes

- £12 million per year developer levy

Again, no public scorecard I could find.

According to Ealing.News, “Employment in Ealing stood at 176,690 in December 2022 before increasing to 182,992 by December 2023, a gain of more than 6,300. Figures for December 2025 show there were 181,325 people employed in the borough, down 2,195 compared with the same month a year earlier.”

The developer levy: a late arrival

The 2022 manifesto promised a new “developer tax” raising £12 million per year.

But the Community Infrastructure Levy was only approved two months ago in December 2025, to begin in March 2026.

Opposition councillors say this followed a 15-year delay and estimate up to £90 million in lost infrastructure funding.

The exact figure is disputed, but the timing is not.

It’s certainly true that by far the largest new development - the massive expansion of the Southall Gasworks site from 3,750 new homes to 8,100 - was approved by the planning committee in November 2025, despite around a hundred local objections.

Another three or four months, and that would have been necessitated Berkeley Group making a very large CIL payment to the borough.

Council tax: the quiet background story

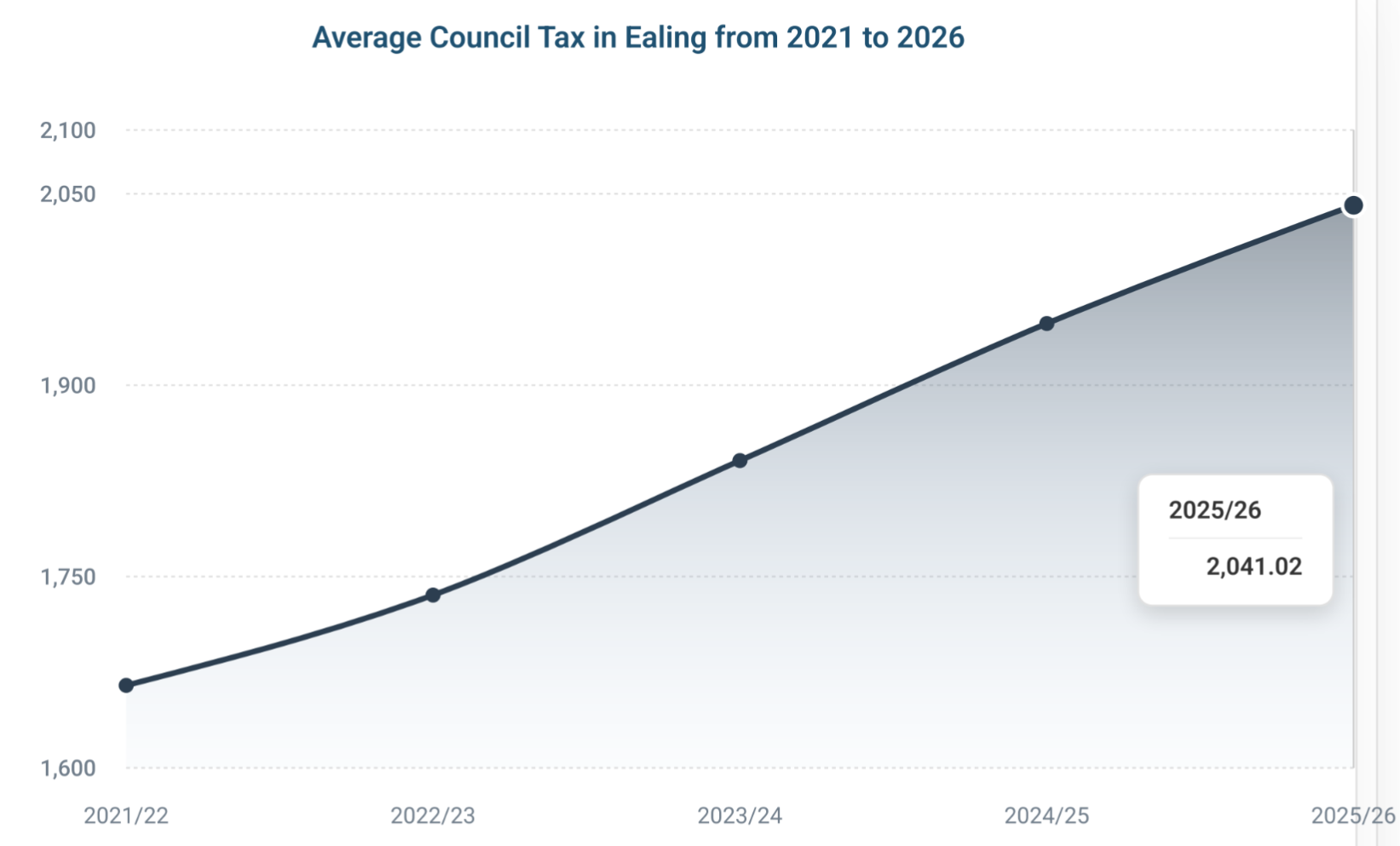

Across both manifestos, Labour presented itself as shielding residents from austerity. But since 2018, council tax has risen repeatedly. Several increases were close to or at the legal maximum. The 2023/24 rise was nearly 5%. The council attributes this to social care pressures and reduced government funding.

The big picture

Under Ealing Labour and under Mason’s watch:

- The housing waiting list rose from 9,000 to 12,000

- 5,000 social homes were demolished

- They have been replaced by far fewer than 5,000 “genuinely affordable homes” (the social rent proportion likely to be much less than 50% of that figure) completed and ready to live in

- Housing targets have been repeatedly missed, and half-built homes will have to be demolished

- Developer tax has been wasted and essential large infrastructure projects were simply abandoned

- All of this while Mason was cabinet lead for housing, planning and transformation while qualifying as a town planner at the prestigious Bartlett School of Planning before he became leader.

He had the expertise. He had the power. He had the resources.

What he lacked was the political will to prioritise residents over developers.

- Council tax has gone up 22% over five years

- Fly-tipping has more than doubled

- It costs more to clean up the rubbish than was saved by switching to fortnightly waste collections in 2016

- Children’s centres cut

- 70% pay rise for Mason

But the gap between slogan and reality was perhaps clearest in environmental policy.

The 2018 manifesto promised to “use our powers, as we have in Acton and Southall, to go after polluting industries that show no regard for the quality of our air.”

One year later, Mason was accepting Berkeley Group hospitality at the MIPIM property developers festival in the south of France, all while Berkeley poisoned Southall residents with benzene and naphthalene at levels way above legal limits.

When residents complained, his response was: enforcement “wouldn’t stack up in court.”

Mason didn’t go after the polluting industry. He went partying with them in Cannes.

Not on your side.

The transparency gap

The biggest difference between the two manifestos is not the promises. It is the absence of a clear, public scorecard showing:

- Which promises were met

- Which were missed

- Which were quietly rolled forward into the next election

Instead, to find answers to make informed choices, residents must dig through Cabinet reports, budget papers, scrutiny documents, and press releases just to piece together partial answers.

The obvious question

Between 2018 and 2022, the housing target rose from 2,500 to 4,000 homes. Between 2022 and 2026, many of the new promises still lack clear public outcomes.

So the question for voters is simple: are targets being delivered? Are manifesto promises being kept? Or are they just getting bigger each election?

And if targets are not being met, and election promises are repeatedly broken, why is that? Because it’s not actually all Peter Mason’s fault. The same happened ten years ago under Julian Bell. The same happened thirty years ago when Virendra Sharma was a councillor before he became an MP.

Peter Mason knows why:

[E]ver since the 1980’s, and Thatcher’s dismantling of the social housing sector, local authorities have been starved of the funding they need to build the next generation of council housing.

Under Blair and Brown’s New Labour, under the Tory/LibDem austerity coalition that forced ordinary people to pay for crimes committed by Wall Street bankers, and under Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, the political will has consistently favoured mega rich housebuilders over the needs of people to live in decent housing.

Change will be hard. And it won’t happen overnight. But the mainstream parties are all gatekeepers for the status quo, developers and the ruling classes.

We need people in local and national government who will actually stand up for the needs of ordinary people.